American artist and ecological art pioneer Alan Sonfist (b. 1946, New York), renowned for over 60 years of artistic exploration, reflects on his journey from Time Landscape in 1965 to his current work with his new foundation, Land Art Forward.

Art of Change 21: You’ve often spoken about the emotional impact that learning about deforestation had on you as a young person, which ultimately inspired your path as an artist. How has this issue evolved in your work over time?

As a young child growing up near the Hemlock Forest in the Bronx in New York, I witnessed its partial destruction, both from fire and human indifference. Despite the constant threat to its survival, the forest was my sanctuary—a place of warmth, security, and a profound connection to the natural world. My paintings and drawings became a visual diary of my experiences there, capturing the forest’s beauty and fragility as it changed with the seasons. I watched the acorns of my childhood tree grow into sturdy seedlings, their leaves carpeting the forest floor, protected by the wind’s gentle embrace. The hollow of the mighty oak appeared often in my dreams, symbolizing the deep bond I shared with the forest and its inhabitants. But even within this tranquility, I couldn’t escape the looming threat of destruction. The indifference and hostility of those nearby cast a shadow over the forest’s vitality.

Growing up later in South-Central Bronx, I became acutely aware of the delicate balance between urban development and nature. Witnessing the destruction of the nearby forest and the relentless expansion of the Cross Bronx Expressway left a profound impression on me. Seeing the effects of urban planning on the natural landscape stirred a profound sadness, which later became a central theme in my artistic work.

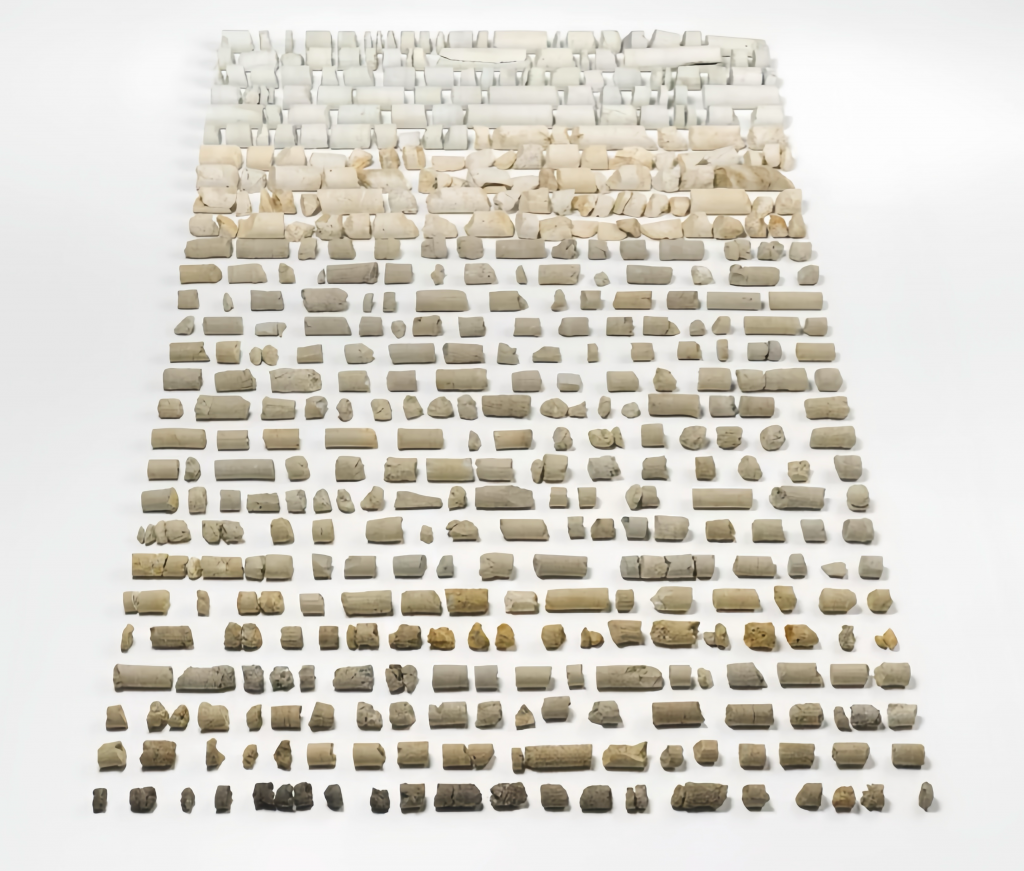

Alan Sonfist, Earth Monument to Chicago, Natural earth drillings, 1971, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Alan Sonfist, Earth Monument to Chicago, Natural earth drillings, 1971, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Your work Time Landscape, an urban forest created in 1965 when you were still young, remains an unparalleled example of ecological art in today’s society. Now that the piece has been somewhat “rediscovered” in light of the growing environmental movement, do you feel that Time Landscape holds a political dimension?

At the age of eighteen, I embarked on the ambitious journey of creating Time Landscape with the support of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) thanks to its deputy Ted Rousseau, who shared a passion for nature. Turning the concept into reality was daunting, leading me to form a team of experts from MIT, including architects and scientists from various fields. Together, we carefully selected species like oak, dogwood, and arrowwood to populate the landscape. Since there were no established guidelines for creating an urban forest in the 1960s, our collaboration was crucial in crafting an immersive experience that reflected the rich biodiversity of a natural forest. Despite initial skepticism about recreating a historical ecosystem, Time Landscape exceeded expectations and thrived. It stands as a monument to nature, honoring the Native American landscape that existed before European colonization, while reminding us of the importance of preserving our natural heritage. It would not have been possible without the support of Jane Jacobs, an early environmentalist, activist, and urban theorist.

The landmark designation of Time Landscape by New York City Parks Commissioner Henry Stern in 1999 marked a significant milestone, solidifying its cultural and ecological importance. This recognition helped inspire similar efforts to reclaim natural habitats within urban settings. Time Landscape serves as a poignant reminder of nature’s fragility and the pressing need for conservation. It is a living testament to the interconnectedness of all life forms. It offers visitors a chance to immerse themselves in biodiversity and reflect on the intricate web of relationships that sustain ecosystems. Its presence in an urban setting raises critical questions about the role of nature in city planning. The allocation of resources for maintaining green spaces, protecting native species, and integrating sustainable practices into urban development are all inherently political issues.

Alan Sonfist, Time Landscape, Indigenous trees, earth, open meadow, 1965-Present

You often use the term ‘magic’, when discussing your works, as if the forces of nature were an endless source of wonder. Could that explain what drove your practice between 1965 and 2025?

Absolutely, the origins of art, for me, trace back to ancient sites like Lascaux, where our ancestors’ cave paintings reflected their profound connection to the natural world. In many ways, I see myself as a modern-day shaman, channeling the ancient wisdom of our forebears and drawing upon the primal energy of the earth in my art. While I may not heal humans in a traditional sense, I am devoted to a different kind of healing—one that focuses on restoring balance and harmony to the planet. At its core, my art serves as a conduit for the earth’s spirit, transmitting its energy and vitality to those who engage with it. By tapping into the ancient wisdom of our ancestors and honoring the sacredness of the natural world, I hope to inspire others to join me in the urgent task of healing the planet and protecting its ecosystems for future generations.

I have created numerous site-specific works around the world, which are powerful evocations of nature and aim to shed light on its poetry. For instance, my installation Birth by Spear in Tuscany, Italy, embodies this intention. These sixty years of work have been possible only because nature has always been a constant source of peace and learning for me. Similarly, Time Capsule of Ancient Forest of Antwerp, created in 2015 for the Verbeke Foundation in Belgium, explores a more futuristic concept: preserving nature within a capsule. I love this image of humanity, like Noah, preserving nature to pass it on to future generations.

Alan Sonfist, Birth by Spear (Minerva thrust the spear and gave birth to the Olive Tree), Indigenous plants, terracotta tiles, stainless steel, 2010, Tuscany, Italy

What are you working on at the moment? What are your current projects?

I just had an installation at Art Basel Miami in December, which will be both a site-specific installation and an experience. It is a collaborative work entitled Rebirth in the Inferno. I conceived it as a message addressed to collectors and visitors. Reflecting my ongoing commitment to the environmental cause, the installation features fragments of a burned forest, arranged to have a commanding presence in the space. Walking around them, you can really feel the tension and energies coming out of them. Life is still here, in a different form and it is our mission to protect it. Before that, I was in Paris for a solo exhibition, Songes Telluriques, at Devals Gallery. The show explored a specific period of my work from 1965 to 1975, focusing on the subterranean qualities of the earth and its energies. I am now focusing on a major project: an installation I created for the Parrish Museum in the Hamptons.

Speaking of collaboration, you also founded Land Art Forward, a foundation and artist collaborative space entirely committed to the environment. Could you tell us more about it?

Alongside scientists, curators, and supporters of the ecological movement, I created this foundation called Land Art Forward. Our aim is to bring artists and scientists together to tackle what I believe is humanity’s greatest challenge: the climate crisis. Our first initiative was a symposium organized in collaboration with the Art, Culture, and Technology program at MIT. For me, Land Art Forward is about understanding the world we live in, and my mission moving forward is to support and mentor emerging ecological artists, empowering them to confront the urgent environmental challenges.

Author: Lorenzo Beatrix

Cover image: Alan Sonfist in Time Landscape, Photo: John Taggart

Other images: Courtesy of Alan Sonfist and Alan Sonfist Studio

Impact Art News, November-December-January #51