French artist Marguerite Humeau (born 1986 in France, based in London) has built a singular body of work that moves between deep time and speculative futures brought into the present, between lost worlds and those still in formation. Settings such as caves, deserts, forests, and post-industrial landscapes become sites of transformation – places in which identities loosen, hierarchies dissolve and other modes of being take form, allowing the possibility of the sublime to surface within conditions of radical change.

On the occasion of her exhibition Scintille at White Cube New York, we spoke with Humeau about darkness and deep time, clairvoyance and geomancy, sacred infrastructures, and the possibility of artworks as active agents and quiet monuments that evolve across centuries.

Your early works often evoke deep geological time and ancient life forms. In your current exhibition “scintille” at White Cube New York, the cave – a symbol of prehistory – reappears, alongside the bat, a creature often associated with archaic or prehistoric imaginaries. Do you see your practice as creating an interface between the present and deep time?

In the context of Scintille, I became deeply interested in the experience of darkness. A year ago, I spent time in Raja Ampat, an archipelago located off the northwest tip of Bird’s head Peninsula in West Papua, where a local guide took us to a cave accessible only by boat, emerging directly from a river. It was an extraordinary experience, a true encounter with the sublime. Inside, there was complete darkness. Its stalagmites and stalactites formed over thousands of years, ecosystems evolving without ever encountering daylight. It felt like traveling into the distant past, but it could just as easily have been the far future. At the same time, the experience was intensely physical, anchoring me in the present. It is that unique physical experience that gave me the idea for the exhibition. I started to connect this feeling of being in the dark with the more emotional side of our uncertain times. I looked closely at the life forms within the cave and associated them with emotional states that might arise from darkness.

In the exhibition, nothing exists as an isolated entity; everything is relational. Bats, for instance, live as colonies, embodying systems of mutual care, nursing not only their own offspring but others within the group. Stalagmites, too, are accumulations of countless drops of water, monuments built slowly through relationship and repetition. This led me to think that in times of darkness, perhaps what matters is not grand, monumental gestures. Perhaps it is about small, sustained acts of care that, over time, become their own kind of monument ; soft, almost imperceptible at first, like water that seems still, yet gradually crystallizes into immense structures.

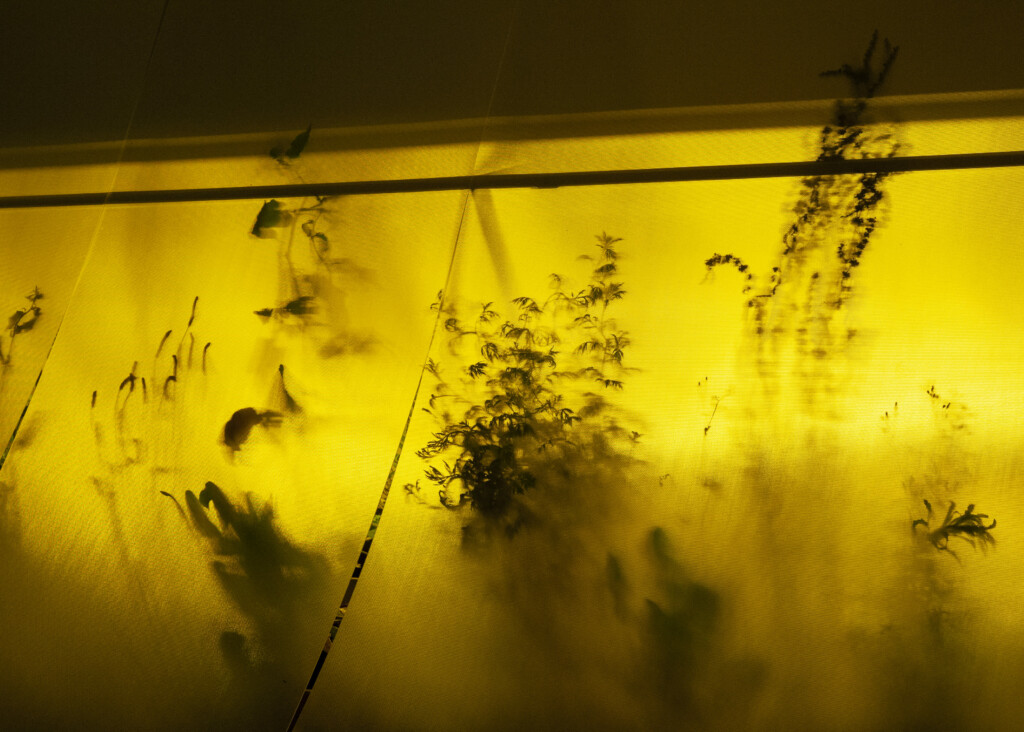

Marguerite Humeau ‘scintille’, White Cube NY 2026 © Marguerite Humeau © White Cube (Frankie Tyska)

It’s interesting that you’re evoking the notion of monumentality and long temporalities and including narratives of other species. Would you say that these interests have led you toward a more monumental approach in your work? I’m thinking in particular of Orisons, for example.

In many ways, all of my work revolves around reactivating extinct beings, imagining worlds that do not yet exist, or exploring parallel presents. My practice consistently engages with movements across time and space: travelling between deep time and distant futures, and between the depths of the Earth and the cosmos.

My project Surface Horizon, presented at Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, began as an exploration of the figure of the clairvoyant. At a time when humanity faces profound challenges, I became interested in the idea that some individuals may possess particular sensitivities or forms of perception that others do not. These are perhaps the voices we should be listening to, those who can help us imagine alternative ways of living.

For me, this was a pivotal moment, because it wasn’t about representing another time or another place, but about focusing on what I call “divinatory instruments”; entities capable of connecting us to other spaces and temporalities. At the same time, I was deeply engaged in research on weeds, whose capacities I find remarkable. Some plants, for instance, grow only in soils that are already damaged; they signal an imbalance, the presence of certain chemicals, or even the onset of desertification. In that sense, they act as indicators of what is to come. I began to think of them as oracles, or forms of clairvoyance themselves. This is how the idea of portals emerged ; entities that embody these connections across time and space.

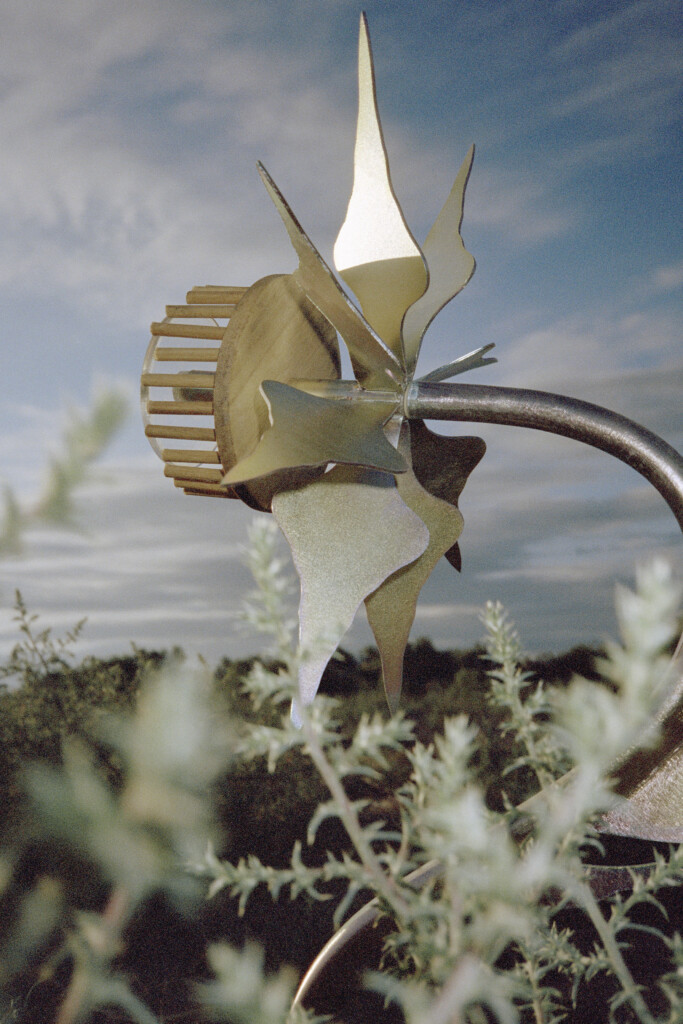

This reflection led me to Orisons. I began to imagine that certain places on Earth might function as portals or territories that connect different times and spaces. I was thinking of sites like Stonehenge and other sacred circles, which eventually led me to consider crop circles.

Around that time, I was reading about Colorado’s San Luis Valley, a region already severely affected by climate change. In 2020, it became increasingly clear to me that some landscapes are experiencing these transformations in very tangible ways. I became interested in the idea that this land could itself act as a portal to a world to come. I started drawing a parallel between the circular forms created by intensive agriculture and ancient sacred circles. It made me wonder whether post-industrial infrastructures might one day be seen as ruins or the “sacred architectures” of our era. From there emerged the desire to transform a site of extraction into a site of reverence.

“Orisons” by Marguerite Humeau, 2023. Photo: Julia Andréone & Florine Bonaventure. Courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Could you tell us a bit more about your work with clairvoyants ?

For this project, I worked with a very specific group of clairvoyants known as geomancers, who focus on reading landscapes. They described the land as if it were a body, identifying points of tension and sharing visions they sensed there – fragments of the past but also possible futures. One of them spoke of the presence of a woman who had died in the 19th century in the northwest corner of the site, as if her spirit were still somehow bound to the place. I was told that perhaps the artwork could help release that presence.

The geomancers suggested that I think of the wind-activated musical instruments I was envisioning as acupuncture needles, to be placed very precisely in specific points of the landscape where they could activate or rebalance certain energies.

For me, this marked an important shift. I became increasingly interested in artworks as active agents rather than passive objects to be looked at. I’m not drawn to making works that function solely as visual forms.

Through my research on plants, for example, I became fascinated by the idea of elixirs ; substances you ingest that transform you from within. I began to imagine artworks in a similar way: pieces that operate internally, that shift something subtle but real. In that sense, the idea connects back to the clairvoyant figure in Surface Horizon at Lafayette Anticipations, where the work also functioned as a kind of perceptual activation rather than a static object. In Surface Horizon, a clairvoyant human presence was guiding visitors through the landscapes and asking them questions such as “what is dormant, in you?”, “what has been lost?”, “what returns?”. Some people would come out in tears, transformed by the experience from within.

Marguerite Humeau The Oracles of the Desert (detail) 2021 Courtesy the Artist, C L E A R I N G New York/Brussels Image Credit: Julia Andréone

We are curious to know more about your latest project you announced with Kistefos, due to open in September 2026. Can it be seen as a continuation of Orisons or is it something completely different?

It continues the thinking that began with Orisons. I was invited by Kistefos before Orisons even opened, and I’ve been developing this project over the past three years. It takes place in Norway, in a spruce forest that was originally planted for paper production. The museum itself is a former paper factory.

In my research, I became interested in the site as a landscape shaped by extraction, and in how it might allow me to deepen my exploration of transforming sites of extraction into sites of reverence. At the same time, I was drawn to another question: what does it truly mean to create a site-specific work? At Kistefos, I’m pushing that idea to a radical, absolute extent. The form, the narrative, and even the way the work evolves all emerge directly from the site itself. That was essential to me. I imagine it as a work that could unfold over centuries, even millennia. It exists at the scale of the forest, without clear boundaries, uncontrolled, and unscripted.

“Orisons” by Marguerite Humeau, 2023. Photo: Julia Andréone & Florine Bonaventure.

Courtesy of the artist and Black Cube Nomadic Art Museum.

Your work engages with other species – animals, plants, even microorganisms. Are you trying to represent them, or to help us see the world from their perspective?

For me, these species are really like companions or guides. Right now, of course, there’s a lot of focus on the climate emergency, but when you look at species like termites, it’s remarkable. They’ve existed for millions of years and survived countless extreme climate changes. That’s why I started studying them. Surely, they know things we don’t, and their ways of adapting are highly relevant. My work involves trying to understand who they are, how they operate, and what we might learn from them.

It’s the same with plants, I see them as guides. The idea of “guides” came to me while working on Surface Horizon at Lafayette Anticipations. I was studying the Doctrine of Signatures, an ancient body of knowledge focused on plants. It looks at a plant’s shape, form, color, and life cycle amongst other things to help humans understand how to relate to it. A famous example is lungwort: its leaf resembles a lung, with white spots like an infection, so it was traditionally used to treat lung diseases. But the Doctrine isn’t a fixed dictionary of plants. It’s more like a decoder, giving tools to interpret any plant that has ever grown. I explored this extensively with one of its specialists, Julia Graves. She had a huge impact on me because looking at the natural world this way really gives you the sense that plants can guide us, that they might know things we don’t. And since we can ingest them, they can literally transform us from the inside, becoming part of our own substance. That’s when I truly began to think of plants as guides.

Earlier, you mentioned the idea of “sacred” places, even ones that have been heavily altered or damaged by humans, like in Colorado or the Norwegian paper forests. Can you explain why you see these spaces as sacred?

I’m not sure if these places are inherently sacred, but I’m interested in how we might transform them into sacred spaces. Maybe they connect more to the idea of the sublime , a concept I have been exploring through many of my works: the juxtaposition of awe and horror. Many of my early works dealt with the concept of a “luminous horror”. Sites of extraction may carry a horror within, and by nurturing them and transforming them, they might become places where the sublime is being experienced.

When I worked with clairvoyants or geomancers, I encountered the idea of a “blind spring”, an underground spring that has never seen the light of day. Many ancient sacred sites are built over these hidden waters.

I’m also working on a grain elevator in Missouri, another site of extraction, and there’s a major blind spring beneath it. Maybe it’s a coincidence, but its presence feels meaningful. The elevator itself, tall and imposing, has a cathedral-like quality. I’m exploring what threads make a place feel sacred.

These infrastructures no longer serve their original purpose, which makes me think about how large human-made structures might hold and process memories at the scale of a city; memories too heavy for humans alone. Perhaps some post-industrial sites can do this work. In that sense, a place can feel sacred because it connects to something sublime. Like Orisons in the desert, the work was a circle, but it was also in a valley with a vast open sky and very dark nights. In that context, it made sense that a post-industrial circle could become a sacred space. It was already a place that felt close to the sublime, with the juxtaposition of the landscape absolute beauty and its expansive, complex histories. In other contexts, transforming the function of a structure can similarly allow for an experience of the sublime.

The clairvoyant’s visions, as part of the “The Oracles of the Desert”, 2021. Credit: Alexia Vénot

Would you say that part of your role as an artist is to explore transformations, evolutions and similar processes ?

Yes, I do. Artists can in a way be seen as super sensitive connectors to the outside world, like receptors or sensors – or, if we image humanity as a single collective organism, artists would be the tips of the fingers. Artists can sense things before they happen, helping us become aware of subtle, unnamed, or unidentified shifts in the world.

Cover image: Marguerite Humeau, 2025. Photo: HAM / Kerttu Malinen. Courtesy of the artist.

Interview by Patricia Friedrich and Eloi Salmon

Art of Change Journal 21, February 2026